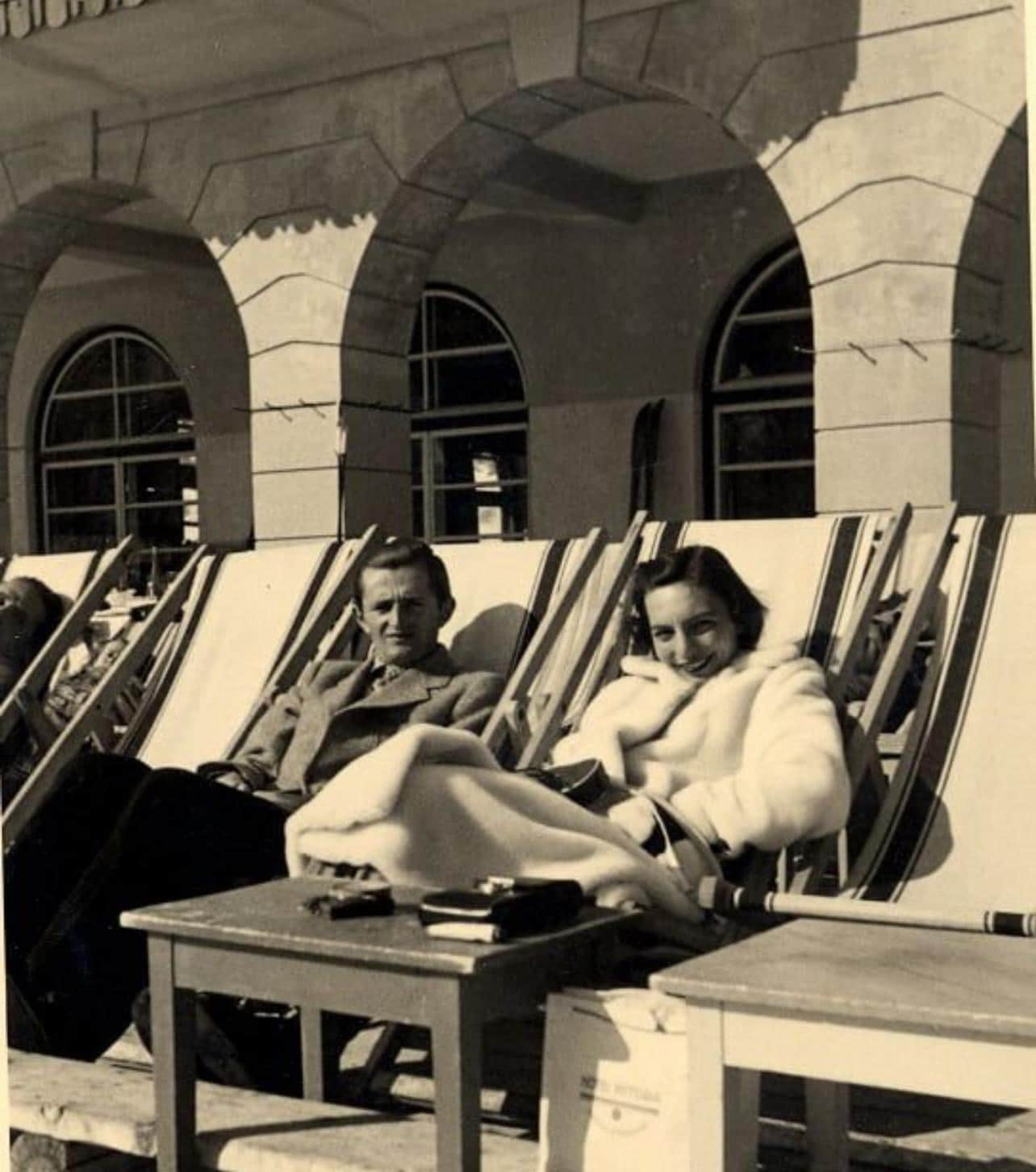

Lea Ypi was scrolling through social media when she stumbled across a black-and-white image of two glamorous newlyweds honeymooning at a luxury hotel in the Italian Alps. In the picture – taken in 1941, as World War II raged – a man reclines beside a woman, draped in fur and smiling warmly. Ypi recognised her instantly: it was her grandmother, Leman Leskoviku. She was struck by the comments beneath it – “communist spy,” wrote one user, “fascist collaborator.” In the days that followed, Ypi found herself returning to the photo again and again. “Why should those people decide – without knowing her, without knowing us – what my grandmother wanted, who she was, what that photo meant?” she writes in her latest book, Indignity. “And what gave them the right to share it, summarise her life and then heap scorn on it?”

Growing up, Ypi lived what she thought was a normal life. She went to school, queued for rationed groceries and sang songs about Uncle Enver Hoxha, the prime minister turned longstanding dictator of Albania – the last Stalinist outpost in Europe. The only abnormality she noticed was that, unlike her classmates’ families, hers refused to hang a picture of Hoxha on their wall or make the obligatory visit to his grave after his death in 1985. Ypi started to ask questions, but at that point, her parents couldn’t give her the answers.

When communism fell in Albania in 1990 and the statues of Stalin and Hoxha were toppled, people could vote freely, worship as they wished and live without the fear of prying ears or secret police once again. A new party promised democracy, freedom. But it wasn’t long before factories began to close, jobs disappeared and a new kind of disillusionment took hold. It was then that Ypi’s hidden family history began to emerge: stories of her grandmother; her husband, the statesman Asllan Ypi, later branded an enemy of the state; and his father, Xhafer Bey Ypi, the tenth prime minister of Albania and a classmate of Hoxha. Their history had been obscured to protect a young Ypi, but any tangible trace of it had otherwise vanished with the empire and war, rewritten with the rise of communism and new nation states in the Balkans.

These revelations shaped Ypi’s lifelong questioning of what freedom really means. Now a professor of political theory at the London School of Economics, she examines how the past informs the present and, in turn, dictates the future of democracy. Her first trade book, Free: Coming of Age at the End of History, is an award-winning memoir that reflects on coming of age during this time of political unrest and the disenchanting transition from one socio-economic ideology to another.

Indignity dissects the concept of freedom, exploring the fragility of truths both personal and political. The book, a hybrid of fiction and non-fiction, uses the imaginary to illustrate how dignity and indignity play out in traumatic, historic circumstances. Drawing on secret police files, spy reports and court depositions found in archives across the world, combined with her own memories of Leskoviku, Indignity is not only a reimagined retelling of her grandmother’s life, but also a meditation on how history is curated, contested and lived.

Here, Lea Ypi talks about freedom, and how Indignity is the story not only of her grandmother but of many, then and now.

Rose Dodd: Indignity not only discusses freedom, but also embodies it with an unconventional form that traverses both non-fiction and fiction. How did you approach writing the book?

Lea Ypi: The motivation behind Indignity was philosophical, starting with the concept of freedom from the angle of my grandmother who, like Kant, saw freedom as moral agency, and looking at how this operates in the context and circumstances of political history. I wanted it to be a hybrid of ethics and esthetics that offers a richer understanding of what dignity or a lack thereof consists of. We don’t usually see or learn about this side of history and politics.

RD: Can you elaborate on the title, Indignity?

LY: Freedom gives people dignity. And having or maintaining it necessitates a capacity for moral agency. So what happens when nothing goes the way the agent wants it to go, when an agent tries to make certain choices but fails? Take my grandmother, for example. Indignity was a way to test these ideas of freedom, demonstrating and putting pressure on the concept of it as moral agency in traumatic circumstances such as in the interwar period, the collapse of an empire, Europe’s political reconfiguration.

RD: What’s marked in both Free and Indignity is this search for belonging and an exploration of identity and heritage.

LY: Absolutely. It problematises identity and the way in which identity is framed or presented to us as this readymade thing for us to either inhabit or refuse to inhabit. The life of my grandmother was a good way of putting pressure on these homogenous accounts of identity, in particular the one Indignity is most concerned with: national identity, which generates a lot of exclusion – even when it looks benign or mellow. My grandmother’s story was one of many that were erased in the post-war period because the new nation states that emerged had to assert themselves, and to assert themselves, they relied on patriotic histories.

RD: The ending, which I won’t spoil, proves that this is just one example of so many stories that have been forgotten or erased.

LY: I hope it draws attention to the voices that are completely lost without the possibility of closure, and in doing so, to the voices that we might be missing now.

“Identity is framed or presented to us as this readymade thing for us to either inhabit or refuse to inhabit” – Lea Ypi

RD: Indignity is your first foray into fictional prose. How was the shift from the very rigid formula of academic writing to the liberty of literature?

LY: It was an interesting way of teasing out all the questions and approaching them from different angles that looking at history and politics academically doesn’t always allow. When writing philosophy, you start with a premise and, if it’s true, you reach a certain conclusion, removing ambiguity along the way. You’re always thinking: What is my argument? What are the positions I need to reject? What’s my conclusion going to be? It’s a much more linear way of writing. In literature, if you start with a premise and end with a conclusion, the writing will be schematic and dry and possibly not very good. Instead, you create characters to problematise your assumptions and demonstrate the argument, and the better you do that – as in, the more individuality, the more particularity, the more ambiguity – the richer the account.

RD: In Indignity, your ‘conclusion’ is quite alternative. There’s not really any closure.

LY: If you see it from the point of view of a granddaughter looking for the truth about her grandmother on an individual level, then perhaps there is no closure, no answer. Maybe that’s frustrating. But many real life stories have no closure.

RD: What does the past say of the present?

LY: My academic study looks at the philosophy of progress in history, searching for a metric that we can use to measure how we learn from mistakes of the past and can apply this progress to solve problems of the present and future. It’s looking at the past in a way that is productive in helping us to avoid the past mistakes. But first, we must identify the problems of the present from a critical standpoint that is not biased by ideology, propaganda or manipulation. Literature and philosophy can help us find the critical standpoint. Sometimes constructing characters is more helpful in understanding how history repeats itself than just looking at the history.

RD: We are victims to the fallibility – and duration – of our own memory. What part does memory play in this?

LY: Memory helps us keep track of what happened in the past, but you have to be mindful that memory itself is biased. We need reliable mechanisms of storing the past. Even archives can be biased. You have to ask: for what reason does this archive exist? What was excluded? What are the stories we don’t know and how can we evoke them? And that’s where fantasy and imagination are important.

Indignity by Lea Ypi is published by Allen Lane and is out now.