“We’re at the beginning of a revolution,” says jury chair Eliza McNitt at the extended reality showcase, part of this year’s Venice Film Festival. But how will today’s artists shape the way we tell stories tomorrow?

The tiny island of Lazzaretto Vecchio in the Venice Lagoon has a long history populated with ghosts – from its 15th-century days as a quarantine island for plague victims to its 1960s incarnation as an exile for stray dogs. Today its airy, low-slung buildings are home to the Venice International Film Festival’s Immersive section, featuring 69 extended reality projects from across the world that are far evolved from the era of cardboard headsets.

Director Eliza McNitt, a New York-based pioneer of the emerging technology, brought the first part of her Spheres trilogy, executive produced by Darren Aronofsky, to the island in 2018 (installation had to be halted for several days, she remembers, when a skeleton was discovered and exhumed). That year, McNitt won the grand jury prize; this year, she served as jury president: “The oldest film festival in the world is embracing this newest form of technology,” McNitt says when we caught up with her in an ice-cream coloured hotel room at the Excelsior, where she was preparing for the red carpet. “Venice centring immersive storytelling alongside cinema by the greatest directors working today is not just validating – it means the artists don’t have to create for a commercial audience, and are able to take incredible risks and push the boundaries of storytelling.”

The artful, eclectic works that make up this year’s selection range in length from six minutes to six hours, taking users into pulsing nightclubs and atop Hong Kong skyscrapers, mining for gold on far-flung planets and deep inside grief-stricken brains. Many are helmed by women: “A lot have been pioneers in this space because it’s a new frontier that is kind of the Wild West, and anyone who has a vision can enter,” says McNitt, whose first VR film imagined falling inside the eye of the Hubble telescope and experiencing the birth, life and death of a star. “There are less boundaries that you have to overcome with VR – I find it to be much more inviting.”

McNitt and her fellow jurors awarded Taiwanese filmmaker Singing Chen the Grand Prize, for her haunting drama The Clouds are Two Thousand Meters Up. Following a bereaved widower’s untangling of his wife’s unfinished novel, it weaves a dark mystery around users, guiding them with clues discovered in newspaper clippings, photographs and diary entries. A project “that seeks to spark empathy across cultures”, as Chen says, it’s a labyrinthine journey into its protagonist’s psyche, allowing participants to free-roam through layers of time, memory and an ancient forest that hides an elusive cloud leopard. Another highlight, Blur, by Craig Quintero and Phoebe Greenberg, uses live actors to escort viewers into a mind-boggling dreamworld where scientific leaps have muddied the boundaries between life and death. A cautionary tale examining, in its creators’ own words, “the human urge to transcend death and the consequences of reshaping life”, the woozy experience features a sheep-headed dancing woman, mysterious lab experiments, surreal dreamscapes and an unexpected cameo from your own, aged doppelganger.

One of the most moving of the Immersive strand’s non-fiction offerings was Chloé Lee’s SXSW-award winner Reflections of Little Red Dot, a soulful meditation on the cultural history of Singapore that entails slotting old slides into a projector at random to bring up a kaleidoscope of memories – of torn-down housing projects, island nature reserves, and long-disappeared villages. Collected by Lee from locals who have lived through the country’s high-speed, disorientating transformation into one of the most modernised societies in the world, it’s a powerful harnessing of imagination and technology. “In speaking with family members and residents, I was ignited by their desire to cherish and showcase the past as the future threatened to eliminate everything they knew and loved,” she says. “I wanted to honour these neighbourhoods beyond the typical filmic documentation methods and so I turned to XR to see how we can remember the significance of places and personal histories in a new way.”

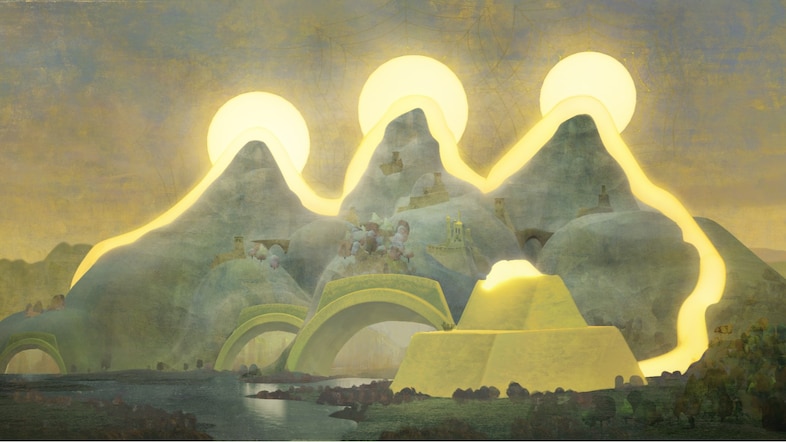

Duo Kristina Buožytė and Vitalijus Žukas felt a similar drive to reinvigorate the past in new ways – in their case, the hallucinogenic artwork of fin-de-siècle painter Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis. With the help of VR, Creation of the Worlds allows users to soar with a flock of birds through the painter’s mythical worlds, encountering sprouting mushrooms, a spiralling walled city and a biblical-strength thunderstorm. After removing my headset, Žukas explains: “We’re trying to bring him back to the world. He was so ahead of his time, it’s hard to believe he was working 150 years ago. Searching for a story inside his pictures, everything is about feeling; bringing a feeling like the original pictures bring you a feeling. It’s not about a storyboard; it’s about emotion.”

Žukas’s description of his project as “an ode to creation” might be a fitting description for the festival’s Venice Immersive project itself. Established by co-curators Liz Rosenthal and Michel Reilhac in 2017, today the six-acre island offers some mind-bending predictions for the future of storytelling. Increasing numbers are taking the two-minute boat ride from the Lido, including The Bourne Identity’s Doug Liman and Conclave director Edward Berger, who both brought VR projects to Venice this year. But in this new space, the most arresting works are coming from artists whose names aren’t yet widely known. “We’re seeing the beginning of a revolution of change, and it is up to artists to define how those tools are used,” says Eliza McNitt. “This is the moment; in a couple months, we’re going to look back and everything is going to be different. In a year, I don’t even know what to expect. So it’s exciting to have this conversation and it’s also terrifying – but that’s why it’s up to artists to be part of the decisions regarding how we’re going to use these tools.”